Before there was incense, before there was ritual, there was breath. There was fragrance. And there was God.

We’ve been taught to think of religious experience in terms of visions and voices. Flashes of divine light, the thunder of God’s word. We talk about “seeing” the truth or “hearing” God’s call. But what if we’ve been overlooking something? What if we’ve forgotten one of the most ancient and intuitive ways of encountering the sacred?

Smell.

In Orthodox Christianity, worship isn’t just an intellectual exercise. It’s a full-bodied experience. The flickering light of candles, the rhythmic prayers, the touch of icons against the lips, the sweetness of communion wine. And then, there’s scent, perhaps the most mystical of all the senses. Unlike sight or sound, which keep things at a distance, scent fills us, enters us, transforms us. We breathe in, and suddenly, we aren’t just observers but participants. We are inside the moment, inside the experience, inside the presence of God.

Fragrance in Scripture isn’t just symbolic

In Scripture, smell is everywhere.

It’s not just a minor detail in the grand narrative of divine revelation, it’s a recurring symbol of presence, offering, and communion. The Bible, especially the Old Testament, describes sacrifices as offerings of a “pleasing aroma” to God (Genesis 8:21, Leviticus 1:9). These aren’t just poetic embellishments or ritualistic formulas. There is something sacred happening here.

The rising smoke and fading fragrance mirror the unseen presence of the divine, an essence that lingers even after the moment of encounter has passed.

The Hebrew term for “pleasing aroma” (reiakh nikhoakh) doesn’t just mean to smell good. It conveys the idea of rest, satisfaction, and acceptance before God (McGuckin, 2012). When Noah, after the flood, builds an altar and offers a burnt sacrifice, Scripture tells us that “the Lord smelled the pleasing aroma” (Genesis 8:21) and responded with a covenant of mercy.

Here, the act of smelling is attributed to God Himself, as if to show that worship isn’t just about duty. It’s about relationship, about something being received and reciprocated.

The ‘Fragrance of Christ’ in the New Testament

This idea deepens in the New Testament, where the Saint Apostle Paul takes it beyond sacrificial offerings and applies it to people themselves. In his second letter to Corinthians, he writes:

For we are to God the fragrance of Christ among those who are being saved and among those who are perishing.

2 Corinthians 2:15

St. Paul doesn’t speak of merely carrying Christ’s image or echo. He speaks of something more intimate: His scent, an imprint that lingers upon us (Cockayne, 2019; McGuckin, 2012). Holiness, in this sense, isn’t just something we believe; it’s something that permeates us, something that spreads. Just as fragrance moves unseen through the air, affecting those who encounter it, so too does the presence of Christ fill the world through those who belong to Him.

But there’s another dimension to St. Paul’s words, fragrance isn’t always welcomed. He continues:

To the one we are the aroma of death leading to death, and to the other the aroma of life leading to life.

2 Corinthians 2:16

The same fragrance, the same presence, can be perceived differently depending on the heart that encounters it. Just as the scent of incense can be sweet to some and overpowering to others, the presence of God can be experienced as either life-giving or unbearable, depending on one’s spiritual state (Cockayne, 2019).

In this way, St. Paul reveals that divine reality itself is never neutral. It demands a response.

The Church Fathers on the Scent of the Divine

The early Church Fathers recognized the significance of fragrance as a means of encountering the divine. They saw scent as a metaphor for the presence of God. Intangible, yet profoundly real.

St. Gregory of Nyssa, in his homily on the Song of Songs, describes how scent reflects the way the divine is perceived through an immaterial faculty. He writes:

In the same way, too, the scent of the divine perfumes is not a scent in the nostrils but pertains to a certain intelligible and immaterial faculty that inhales the sweet smell of Christ by sucking in the Spirit.

St. Gregory of Nyssa, Homily 1 (2012).

He emphasizes that the perception of the divine isn’t physical but spiritual.

Just as fragrance lingers even after its source has disappeared, so too does God’s presence remain perceptible through the soul’s spiritual faculties.

He further expands on this analogy:

The divine power is inaccessible and incapable of being contaminated by human thought processes. It is as if by certain traces and hints that our reason guesses at the Invisible; by way of some analogy based on things it has comprehended, it forms a conjecture about the Incomprehensible. For whatever name we may think up to make the scent of the Godhead known, our theological vocabulary refers only to a slight remnant of the vapor of divine fragrance.

St. Gregory of Nyssa, Homily 1 (2012).

For St. Gregory, the experience of God is indescribable, our human language and reasoning can only grasp traces of divine reality, much like catching the lingering scent of a perfume whose source is beyond reach.

Just as fragrance spreads through the air and can only be sensed rather than contained, divine knowledge also surpasses human comprehension. The mind perceives only hints and remnants, never the full reality of the divine essence.

The scent of holiness remains, inviting the soul to pursue what can’t be grasped, drawing the believer toward God through an awareness that transcends words and definitions.

The Fragrance of the Holy Spirit

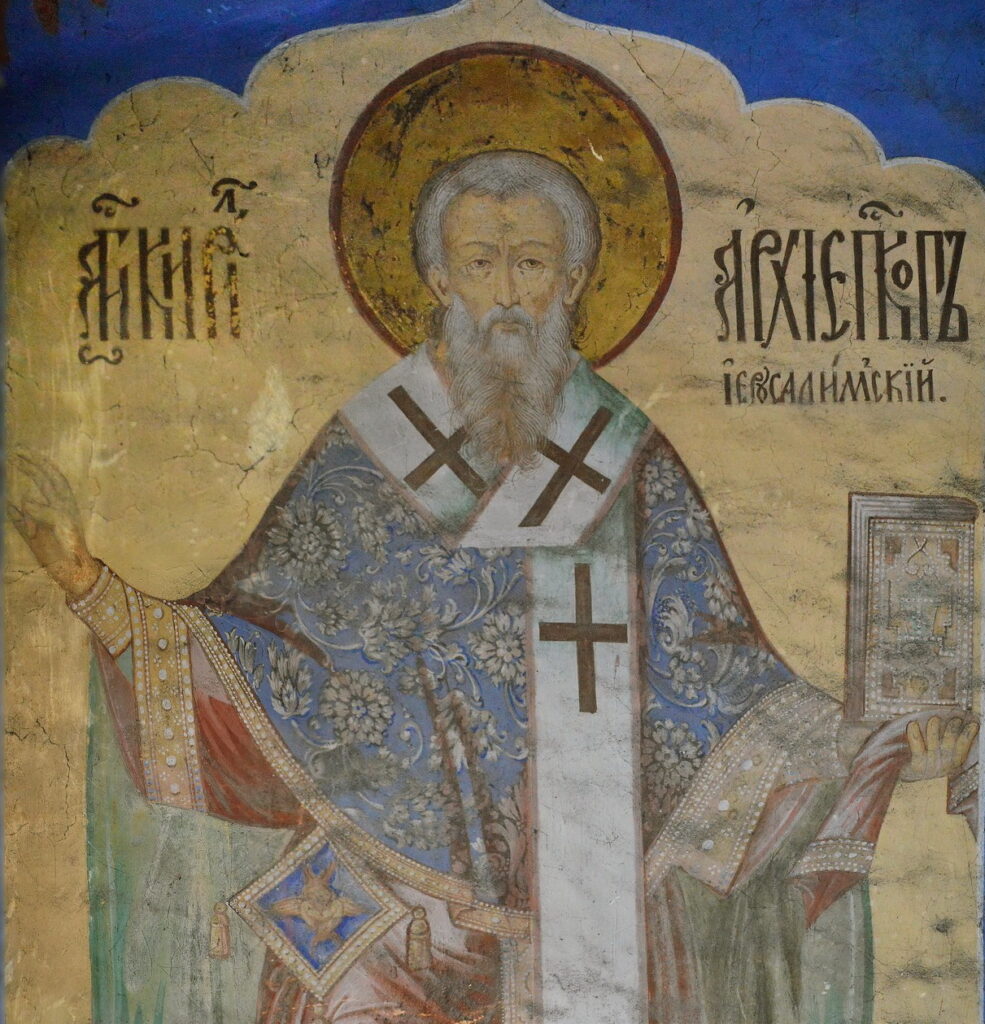

Other Church Fathers extended this idea even further. For example, St. Cyril of Jerusalem also employs the metaphor of fragrance to describe the work of the Holy Spirit. In his Catechetical Lectures, he writes:

First, His (Holy Spirit) coming is gentle; the perception of Him is fragrant; most light is His burden; beams of light and knowledge gleam forth before His coming.

St. Cyril of Jerusalem, Lecture XVI (1838).

St. Cyril contrasts the arrival of the Holy Spirit with the violent possession of demonic forces, emphasizing that the Spirit’s presence is gentle, luminous, and fragrant, something we perceive rather than impose.

He further describes the effect of the Spirit on those preparing for baptism:

O you who are about to be enlightened, you are already gathering spiritual flowers to weave into heavenly crowns, and already the fragrance of the Holy Spirit refreshes you.

St. Cyril of Jerusalem, Procatechesis (1994).

Here, fragrance serves as a symbol of renewal and preparation for divine union. The Holy Spirit, much like a perfume that refreshes and transforms the air, works invisibly to sanctify the soul.

Throughout Christian history, there have been countless accounts of physical fragrances accompanying moments of deep spiritual experience—whether during prayer, the veneration of relics, or the presence of holy individuals (Martin, 2015; Stevens, 2016).

In the tradition of the Church Fathers, these experiences aren’t merely sensory but deeply theological, offering a glimpse of divine presence in the material world.

The power of fragrance—memory, presence, and transformation

There’s a reason why we instinctively associate certain smells with sacredness.

Fragrance operates in the realm of memory and presence, it connects us to places, to moments, to things unseen (Cockayne, 2019). We don’t just remember a scent: we relive it. A particular fragrance can transport us instantly to childhood, to a distant place, to an emotion we hadn’t felt in years. It bypasses rational thought and goes straight to something deeper.

In Orthodox theology, this is no accident. The world is sacramental, infused with meaning, and our senses aren’t just receptors but pathways to the divine. The Church teaches that experiencing God isn’t just a matter of thought; instead, we encounter Him, breathe Him in, and immerse ourselves in His presence (McGuckin, 2012; Stevens, 2016).

This is why the Church has never abandoned the use of scent in worship. Long before Christian liturgies mentioned incense, Scripture describes the Temple as filled with fragrance—from the anointing oils of the priests (Exodus 30:22-25) to the scented woods of Lebanese cedars used in its construction (1 Kings 5:6).

Worship was meant to envelop the whole person: body and soul.

In the same way, the modern Orthodox church retains the power of fragrance. Not as a simple decoration, but as a direct participation in divine mystery.

The scent of beeswax candles, the faint trace of myrrh lingering on an icon, the deep, resinous aroma of frankincense, they all do something to the worshiper. They shape perception, making the invisible tangible. Through them, we remember that we are in sacred space, in sacred time.

And even outside the church, the theology of fragrance remains.

Holiness, once encountered, lingers, just like a perfume that refuses to fade. It changes the way we perceive the world, the way we move through it. It transforms our presence into something that carries the scent of another reality, and others can recognize it, even if they don’t yet understand it.

Because holiness doesn’t just stay in one place.

It spreads.

Breath, spirit, and the scent of holiness

There’s another layer to this. Smell isn’t just something we passively experience. It’s intimately tied to breath, to life itself.

From the very beginning, Scripture makes this connection clear. In Genesis 2:7, God breathes into Adam’s nostrils, and only then does he become a living being.

This is more than simply lyrical imagery; it conveys a deep truth: life itself starts with inhalation, when a holy breath fills a void. In this sense, breathing is more than just survival; it’s, in a sense, a continuous engagement with the divine presence.

The Hebrew word for spirit, ruakh, carries this dual meaning, it signifies both breath and wind, something both tangible and invisible, fleeting yet essential. The Greek word pneuma does the same (McGuckin, 2012). This linguistic overlap doesn’t seem to be an accident; it speaks to something deeper. That breath isn’t just physical, but spiritual. Every inhale is an act of reception, a drawing in of something greater than ourselves.

But this is where it gets even more mysterious.

The scent of holiness as a sign of Divine Grace

The Orthodox tradition has long taught that some saints, through their deep closeness to God, exude a mysterious and unexplainable sweet fragrance (Stevens, 2016; Martin, 2015). Throughout Christian history, people have recorded this “fragrance of holiness”. Some saints’ relics remain incorrupt, and their bodies emit a perfume that defies explanation.

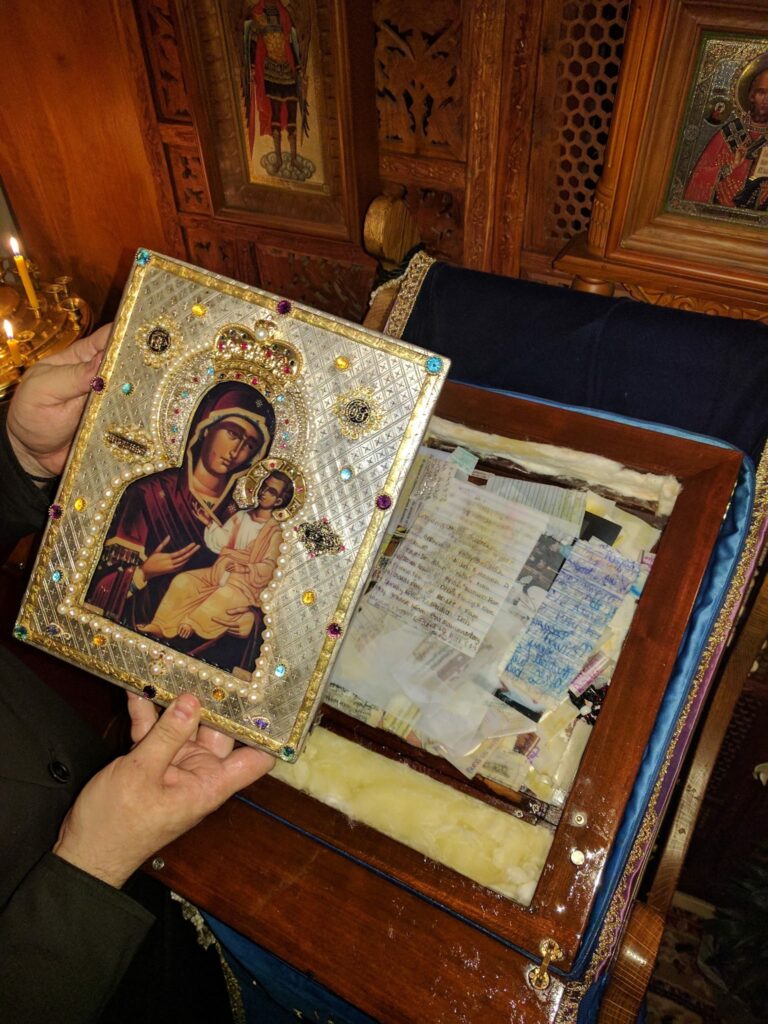

Myrrh-streaming icons, relics, and the bodies of holy individuals have all been described as carrying a scent untouched by time, lingering beyond decay. Many believe this fragrance is a sign of divine grace, a tangible presence that continues even after physical death (McGuckin, 2012; Cockayne, 2019).

Unlike incense, which people deliberately burn to produce aroma, these fragrances emerge on their own, without human intervention, revealing a direct manifestation of the sacred.

It’s as if holiness itself has an aroma, a tangible imprint left on the world. A presence that can be sensed, breathed in, and encountered, not just with the mind but with the body.

And perhaps, in some way, this shouldn’t surprise us. If sin carries its own stench and death brings decay, why wouldn’t sanctity emit its own fragrance?

Why wouldn’t the divine leave behind a trail of perfume?

For those who draw near, its presence is unmistakable.

A transformation of the senses

In Orthodox spirituality, salvation isn’t just about believing something. It’s about becoming something.

It isn’t merely a shift in thought or an intellectual assent to doctrine; it’s a metamorphosis of the whole person, a reorientation toward God that affects every dimension of existence.

Salvation isn’t just about the afterlife; it’s about restoration here and now, about healing what was broken, transfiguring what was darkened, and returning to the fullness of what it means to be truly human. And that transformation doesn’t occur in the intellect alone. It includes the senses, the way we connect with and experience the world around us.

We aren’t just souls floating through existence, waiting for some abstract enlightenment.

We are embodied beings, meant to see, hear, taste, touch, and smell holiness. In the Orthodox tradition, being human means immersing oneself in a world where grace transfigures everything, and even the air around us testifies to God’s presence.

This is spiritual theosis—the gradual transfiguration of the human being into communion with God.

Through divine grace, our eyes are purified so that we might perceive His light rather than remain blind to it. Our ears attune to His voice rather than drowning in the noise of the world. And yes, our sense of smell is sanctified too. For just as sight, hearing, and touch are restored in Christ, so too does our ability to sense the sacred fragrance of divine presence become heightened.

Perhaps this explains why some mystics have described moments of deep prayer as being accompanied by an unexplainable fragrance with no visible source, yet undeniably present (Stevens, 2016; Martin, 2015).

Not a symbol. Not an illusion.

A real experience of something beyond human comprehension.

Restoring the sacred sense of smell

We live in a world that has trained us to tune out our noses. We value what we can see, what we can measure, what we can rationalize. But in the Orthodox tradition, people have never dismissed the sense of smell as mere ornamentation.It remains a pathway to the divine.

Even before the first grain of incense is burned, before the holy oil is poured out, the olfactory sense is already attuned to divine mystery.

Next time you walk into an Orthodox church, take a deep breath.

Let the air fill you.

The air carries the warmth of beeswax, the aged breath of ancient wood, and the whisper of myrrh. This is more than mere ambiance. Think of it as an entryway, a veil between the seen and the unseen, where the sacrum becomes perceptible and eternity lingers, waiting to be inhaled.

Aroma isn’t merely a reminder of the sacred. It’s the sacred itself, woven into the air, waiting to be breathed in, waiting to transform.

Konstantyn Petertil

Aromatherapy specialist and writer exploring the sacred, scientific, and sensory dimensions of scent.

References

Cockayne, J. (2019). Smelling God: Olfaction as Religious Experience. University of St. Andrews.

Cyril of Jerusalem. (1838). The catechetical lectures of S. Cyril, Archbishop of Jerusalem, translated, with notes and indices. John Henry Parker; J. G. and F. Rivington.

Cyril of Jerusalem. (1994). Lectures on the Christian sacraments: The Procatechesis and the five mystagogical catecheses (F. L. Cross, Trans.). St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

Gregory of Nyssa. (2012). Homilies on the Song of Songs (R. A. Norris, Trans.). Society of Biblical Literature.

McGuckin, J. A. (Ed.). (2012). The encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Wiley-Blackwell.

Martin, J. (2015, July 9). The history and meaning of incense. HTP Bookstore Blog.

Stevens, A. (2016, June 15). The smell of holiness: Incense in the Orthodox Church. Mt. Menoikeion Seminar.